The penultimate lecture — Set #5 — in Herbie Hancock’s “The Ethics of Jazz” was held on March 24, with an examination of how the principles of Buddhism connect to human creativity.

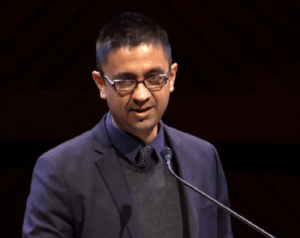

The lecture began with an introduction by Vijay Iyer, a musical multi-hyphenate — jazz pianist/composer/electronic musician/writer/producer — and a recent addition to the Harvard music faculty. Professor Iyer lauded Mr. Hancock and his accomplishments, saying:

The lecture began with an introduction by Vijay Iyer, a musical multi-hyphenate — jazz pianist/composer/electronic musician/writer/producer — and a recent addition to the Harvard music faculty. Professor Iyer lauded Mr. Hancock and his accomplishments, saying:

“We are here because of the shining example he has set, for more than five decades, in a lifetime of galvanizing creativity; astonishing virtuosity; fearless experimentation in rhythm, melody, harmony and music technology; the constitutive influence he has had on American music, or, more to the point, on the sound of modernity itself; the profound humanity expressed in every sound he makes . . . Simply put, he is one of the baddest dudes on the planet.”

Vijay Iyer went on to briefly discuss Herbie Hancock’s worldview, informed by Mr. Hancock’s Buddhist practice, “. . . which is probably to say [that] one’s sense of self is bound up in the lives of others.”

As a result of that view, he said, Professor Hancock’s music represents “an endless series of relational possibilities reflecting a life among people. This non-singularity of being is discernible in Professor Hancock’s vision of community . . . Similarly, Hancock described [early international jazz festivals he participated in] as exercises in ‘learning to live together and respecting all people.’”

As a result of that view, he said, Professor Hancock’s music represents “an endless series of relational possibilities reflecting a life among people. This non-singularity of being is discernible in Professor Hancock’s vision of community . . . Similarly, Hancock described [early international jazz festivals he participated in] as exercises in ‘learning to live together and respecting all people.’”

Mr. Iyer wrapped up his comments thusly: “The commitment not to be a single being also denotes an orientation towards self-transformation, renewal, becoming . . . As [Herbie Hancock] told us a couple of weeks ago, you are the most powerful when you are in the moment. You create the future when you are in the moment.”

Professor Hancock then took the podium for his fifth Norton lecture, this one titled, “Buddhism and Creativity.” He shared several personal anecdotes about how he came to practice Nichiren Buddhism and the positive impact it has had on his own life and that of his close friends and family.

On the relationship between his spiritual practice and the creative process, the Norton professor explained: “Buddhism doesn’t write the notes for me, but it absolutely and positively affects how I look at everything. Buddhism is uncovering and leading a creative life, and, in the process, establishing your own story. A common viewpoint holds that one’s destiny is predetermined by external forces. However, the practice of Buddhism can break through that notion and carve out the kind of life where you’re the author of your book . . . Practicing Nichiren Buddhism reveals a major shift in perception of the relationship between you and the external environment . . . The conventional perspective makes us a slave to the environment . . . The reality is that [the cause of your circumstances] is within your own life, and you have the innate power to transform yourself and advance, expand, and develop a happy life for yourself and others through this practice. A new clarity . . . opens up great inspiration for creativity.”

Professor Hancock then gave a personal definition of the term creativity. “For example,” he said, “creativity isn’t limited to my music. It encompasses what I say, how I act, my perceptions — and it is the process involved in living an inventive, inspired, and meaningful life . . . All of us have the capacity to be creative, artistic individuals, although some of you may shake your head and think, “No way! Not me!” Expanding your personal viewpoint will affect your daily life and influence your purpose. This is an artistic endeavor in which we are all involved; it’s called ‘The Art of Living.’”

“Practice,” Mr. Hancock said regarding Nichiren Buddhist teachings, “creates an inner transformation of our character that helps highlight our humanity and modify our state of being. We call this ‘human revolution’ . . . My life mentor, Daisaku Ikeda says, ‘Wisdom is stimulated by compassion.’ He says, ‘Let us give something to each person that we meet. Joy, courage, hope, assurance, or philosophy, wisdom, a vision for the future — let’s always give something.’ . . . [Mr. Ikeda] also said, ‘We are not born into this world to suffer and be miserable. We are born to be happy and savor true joy; never allowing any suffering or misfortune to defeat us.’”

He continued: “Every human being experiences suffering and one of life’s pivotal challenges is how to turn a negative experience into something of value. When you’ve fallen to the ground, use the ground to get back up again.”

From here, Professor Hancock developed a central theme of this set — the vital idea that creativity isn’t limited to the realm of professionals, emphasizing: “Often creativity is a word associated with individuals from the world of the arts as though these mere mortals are the ‘chosen ones,’ but . . . creativity is in the eye of the beholder.”

From here, Professor Hancock developed a central theme of this set — the vital idea that creativity isn’t limited to the realm of professionals, emphasizing: “Often creativity is a word associated with individuals from the world of the arts as though these mere mortals are the ‘chosen ones,’ but . . . creativity is in the eye of the beholder.”

He then ticked off several components of creativity: “First, is inspiration, which is a good synonym for creativity. It’s that ‘Eureka!’ moment that gets the gears in motion. Next, hard work . . . Challenge is a constant in my life, and if the challenge isn’t readily apparent, I create one. Another characteristic is the never-give-up spirit, which goes hand in hand with courage. It means having the true grit to keep moving forward. Saying, ‘I can do this’ actually encourages ideas.”

Motivation, he said, was another key factor: “What actually motivates creativity? Well, anything under the sun can be a motivator, but here are a few examples. I know several people who feel they can’t create without fear. As long as you aren’t blocked by fear and have the conviction you can overcome it every time, it ceases to be an adversary and you have actually ‘turned poison into medicine.’ Pain and suffering can produce tortured-but-brilliant prose and poetry and gut-wrenching music, obviously. When creativity emerges, it can transform into liberation.”

Professor Hancock singled out other factors — justice, righteous anger, desire, humor, observation and joy — all of which can fuel creativity, and then summed up with: “And last, but not least, is imagination, which is, of course, a characteristic of creativity. Albert Einstein said, ‘Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited to all we now know and understand. While imagination embraces the entire world and all there ever will be to know and understand.’”

Professor Hancock singled out other factors — justice, righteous anger, desire, humor, observation and joy — all of which can fuel creativity, and then summed up with: “And last, but not least, is imagination, which is, of course, a characteristic of creativity. Albert Einstein said, ‘Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited to all we now know and understand. While imagination embraces the entire world and all there ever will be to know and understand.’”

“Sometimes a creative solution can emerge from rethinking an existing pathway or exploring an overlooked idea that was a result of the narrow perspective of conventional thinking . . . I truly believe that my life as a musician and a human being has been profoundly transformed by the impact of Buddhism on my music and my life.”

Professor Hancock then used this theme to launch into the lecture’s conclusion, musing on what it means to live “a creative life”: “It’s a life that we’re all capable of creating . . . there’s no essential difference between artists of culture and everyone else. A person who can live with imagination, hard work, innovation, along with integrity, wisdom, and compassion — in spite of their difficult circumstances — can be a profound contributor toward the creation of a harmonious, human orchestra of life . . . And I hope all of us can agree that we are all artists playing the music, writing the script, or painting the picture of our lives. Concerning the mastery of an art form, I believe that the art of living is, beyond a shadow of a doubt, the most difficult to master.”