The United Nations hosted an event that featured a lecture entitled “A Conductor Stands Up for Justice: How Toscanini Fought Hitler’s Persecution of the Jews” presented by the conductor, Cesare Civetta on April 28, 2015 at the United Nations Headquarters.

Cristina Gallach, United Nations Under-Secretary-General for Communications and Public Information applauded Mr. Civetta’s talk and the brilliant artistry of the Maestro, which inspired the representatives of the international community and the Holocaust survivors and their families in attendance.

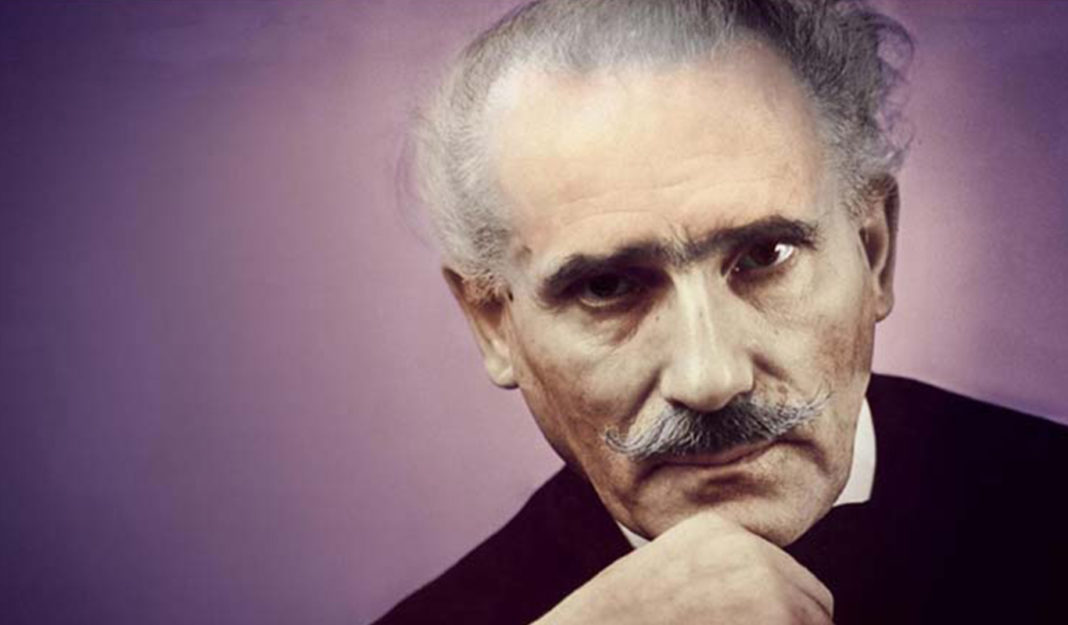

Cesare Civetta has conducted more than 60 orchestras throughout the world. He recently spoke about the inspiration he derives from the Italian conductor, Arturo Toscanini (1867-1957).

Cesare Civetta has conducted more than 60 orchestras throughout the world. He recently spoke about the inspiration he derives from the Italian conductor, Arturo Toscanini (1867-1957).

Q: For your book, The Real Toscanini: Musicians Reveal the Maestro, you interviewed 50 musicians who worked with the conductor. What first attracted you to Toscanini?

CC: When I was 12, I began comparing different conductors’ recordings of the Beethoven symphonies. I kept logs of timings and metronomically tracked the speeds at which the music was played at intervals of 30-60 seconds. I was fascinated by the differences between various conductors. This self-directed research expanded exponentially at 15 when I started college and began programming classical music for the New York radio station WFUV where there were thousands of recordings to listen to!

When I was 16 I met my mentor, Robert Hupka, a Viennese photographer and musician that had escaped the Holocaust. Hupka photographed Toscanini in rehearsals and recording sessions for 20 years. And he possessed many recordings of Toscanini’s rehearsals and performances, which he eagerly played for me on state of the art equipment.

His grandfather was the composer and pianist, Ignaz Brüll, who was an intimate friend of Brahms. Hupka’s insight into Toscanini’s greatness was very perceptive, and during our frequent sessions, which sometimes lasted 12-14 hours, he pointed out important, specific details. Hupka introduced me to some of the musicians who I interviewed for a 35-part radio series about Toscanini. And as a music major in my teens, it was a unique opportunity to ask the highest paid musicians on the planet why Toscanini was so legendary, how he achieved his results and why they unanimously considered him to be in a class of his own.

Q: Was it helpful to you as a budding conductor to speak with these wonderful musicians?

CC: Yes, because the musicians I interviewed had played with the world’s most celebrated conductors. They generously shared an incredible amount of knowledge and wisdom with me.

Q: What was Toscanini’s involvement with Hitler?

CC: Toscanini was admired, among others, by Verdi, Puccini, Strauss, and Debussy, and he was the favorite conductor of the Wagner family. By the 1930’s he had become the most famous musician in the world and was a household name. Toscanini was a vehement anti Fascist.

When Hitler became chancellor of Germany at the end of January 1933, he quickly began dismantling democracy in Germany. Toscanini became greatly alarmed and sent a telegram to Hitler protesting the dictator’s racial laws persecuting Jews, which was published on the front page of the New York Times. He canceled his scheduled appearances to conduct in Germany at the international Wagner Festival at Bayreuth that summer and never set foot in Germany again. Mussolini had entered into an alliance with Hitler and adopted anti-Semitic racial laws in Italy. As the head of La Scala, the most prestigious opera theatre in Europe, Toscanini was a strong, vocal opponent of the Italian dictator. As a result, the conductor was physically beaten, his phone was tapped, his mail read, his house was placed under 24-hour surveillance, and twice, his passport was confiscated. He boycotted Italy and Austria and spent 8 years in exile. Because of his celebrity, Toscanini’s protests were international headline news.

Q: He was obviously an artist of strong moral conscience.

Q: He was obviously an artist of strong moral conscience.

CC: He did more: At the end of 1936 Toscanini traveled to Tel Aviv for more than a month to train and conduct, gratis, the inaugural concerts of a new orchestra of Jewish refugees who had escaped Nazi persecution in Europe, now known as the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra. He returned the following year to conduct additional concerts. And he helped many Jewish musicians obtain jobs, homes, and entry visas in the U.S. As he put it: “I had to show my solidarity. It is everyone’s duty to help in this cause according to one’s means.”

Daisaku Ikeda wrote: “Toscanini was not able to separate art from daily life. For him, pretending not to see injustice was not only stifling to his humanity but fatal to his art. When one’s spirit is twisted, one’s backbone is twisted as well. It was Toscanini’s solid conviction that his daily actions must reflect his conscience.” (Daisaku Ikeda, “Recollections of my meetings with world figures: Carlo Maria Badini, Superintendent of La Scala”, translated from Seikyo Shimbun (Tokyo), October 22, 2000.

Q: What are the biggest lessons you have learned from Toscanini?

CC: I am fascinated by his sense of rhythm, by his fluctuation of the pulse, which at times was done in a very subtle, masterful way—almost un-noticeable. I am inspired by his humility towards his art. His habit of constant self-reflection is most impressive: he would ask others what they thought of a particular detail of the performance. His desire was to always improve, even in his eighties. He was rarely satisfied and always wanted to do better. His philosophy was that he had a responsibility to the composer, and that it was the composer who deserved the applause, not Toscanini; he considered himself to be merely a re-creative artist.

The oboist, Robert Bloom told me about visiting the aged maestro one day at his home. Bloom noticed that the elderly conductor seemed very tired, and after discussing the business at hand, Bloom suggested that they forgo their planned lunch so Toscanini could rest. The maestro explained that he had slept very little the night before because he had been studying the symphony scheduled for that week’s upcoming concert. The symphony was Beethoven’s 5th! When Bloom asked how many times Toscanini had conducted it, guessing 100, 150 times—Toscanini replied that he had indeed conducted it many, many times, but he wanted to re-study it in case he had missed something.

The oboist, Robert Bloom told me about visiting the aged maestro one day at his home. Bloom noticed that the elderly conductor seemed very tired, and after discussing the business at hand, Bloom suggested that they forgo their planned lunch so Toscanini could rest. The maestro explained that he had slept very little the night before because he had been studying the symphony scheduled for that week’s upcoming concert. The symphony was Beethoven’s 5th! When Bloom asked how many times Toscanini had conducted it, guessing 100, 150 times—Toscanini replied that he had indeed conducted it many, many times, but he wanted to re-study it in case he had missed something.

The cellist, Alan Shulman recalled a rehearsal when Toscanini was 86: “We were doing the slow movement of Beethoven’s ‘Eroica’ Symphony, the Marcia Funebre. When we finished it, he stopped for a minute, and said, ‘Gentlemen, I have been conducting this music for fifty years. I do it male. I do it badly. Please, may we do it once again—not for you, but for me.’ Well that’s a big man.”

Q: What are you currently working on?

CC: I am founding a new symphony orchestra in New York City: the Beethoven Festival Orchestra, whose mission is to present first rate performances of great symphonic music, and concert versions of opera for the same price as a movie ticket, and students and seniors, half price. It’s named after Beethoven because he wrote in a letter “My art shall be exhibited for the sake of the poor.” He intended his music to be for everyone. A very good seat at the Metropolitan Opera in New York now costs $535 per ticket. Therefore this kind of music is often presented exclusively to the elite. I intend to change that.

Q: It has been more than half a century since Toscanini’s death in 1957. How is he relevant to the world today?

CC: At the United Nations event I was asked what it is that famous young artists today can learn from him. Toscanini created the most value out of his international fame by using it to draw attention to injustice. He courageously spoke out loudly, and countered the evil of Fascism by launching what has become one of the great orchestras, the Israel Philharmonic. He is a wonderful moral example of great human character.

I am also giving multi-media presentations on other legendary artists who used their art to speak out against terrible injustice: Pablo Casals lived almost half his life in exile and for many years refused to perform, in protest to Franco, the dictator of Spain. Dmitri Shostakovich, the pre-eminent composer of the Soviet Union protested against Stalin’s anti-Semitism through his music. In the 1930s, Charlie Chaplin wrote and financed the production of his anti-Hitler film, The Great Dictator, to warn the world about Hitler. Pete Seeger wrote and performed songs that galvanized the civil rights movement, and the protests against the war in Vietnam. And Louis Armstrong, the father of jazz, created international attention when he lashed out against the government during the struggle for desegregation in Arkansas in 1958.

Q: They are all artists for peace, aren’t they? And we are all artists for peace in our own unique way. Thank you very much.