(Many thanks to Peter Dorbin and the Philadelphia Inquirer for permission to use this article.)

November 25, 2012

By Peter Dorbin, Inquirer Culture Writer (Philly.com)

Would the symphony orchestra be better off if it somehow could be sequestered from such outside concerns as politics and money―the greatest idealization of humanity cut off from humanity itself?

Would the symphony orchestra be better off if it somehow could be sequestered from such outside concerns as politics and money―the greatest idealization of humanity cut off from humanity itself?

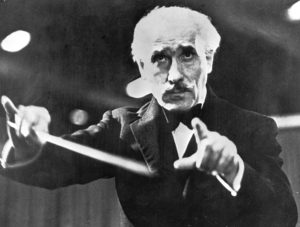

Such compartmentalization was not possible for Arturo Toscanini. On the day Hitler’s troops entered Vienna in 1938, the great Italian conductor stormed out of rehearsal with his NBC Symphony and into his dressing room. “There he barred the door to his family and friends,” according to a story retold in Cesare Civetta’s recently released The Real Toscanini: Musicians

Reveal the Maestro (Amadeus Press).

“He threw scores on the floor, turned over chairs, kicked the table, tore at his clothes, and wept. For hours he went through this solitary lamentation.” The scene spoke, in a way, for Toscanini’s entire career. The conductor who would obsess for decades over a single note in a score was also a stalwart globalist, defying Mussolini and Hitler at cost to his career, getting beaten up―literally―for refusing to conduct a fascist anthem, donating money to early Israel and World War II charities.

“Toscanini was not able to separate art from daily life,” said the Buddhist sect leader Daisaku Ikeda. “For him, pretending not to see injustice was not only stifling to his humanity but fatal to his art.” The connection between art and the larger world is viscerally sensed in The Real Toscanini.

It also suggests a way forward for an institution in trouble. Whether or not the orchestra today would be seeking greater relevance were its fortunes not in decline, the idea of making connections outside the concert hall, explored in the Toscanini book and two other new titles, now has undeniable momentum.

The Berlin Philharmonic does not just visit Carnegie Hall and leave; it also stops in Harlem to perform with students. El Sistema’s star ensemble, the Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela, which plays the Kimmel Center Dec. 5, lifts its young musicians from lives of poverty and chaos, and is more significant as a social phenomenon than a musical one, its evangelists argue. The West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, started by Daniel Barenboim and Edward Said, is matchmaker to Israeli and Arab musicians. Toscanini’s spirit today infuses the orchestra’s embrace of society.

Most of Civetta’s book is devoted to transcripts of interviews about musicianly matters with those who played under him―his musical philosophy, rehearsal technique, legendary musical memory, and devotion to the composer’s wishes. Woven throughout, though, is the portrait of a man whose saw music as something bigger.