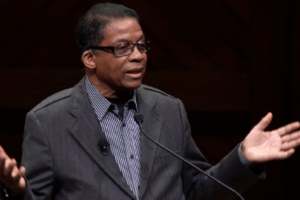

Courage and responsibility are the hallmarks of the rule breakers, says Professor Hancock. With a spotlight on the concept of courage, Herbie Hancock delivered the second of six Harvard University lectures on Feb. 12. Titling his talk “Breaking the Rules,” Mr. Hancock, who is Harvard’s 2014 Charles Eliot Norton Professor of Poetry (and ICAP co-president), captivated a late-afternoon crowd at the iconic Sanders Theatre.

An introduction to the lecture was delivered by Dr. Osvaldo Golijov, Loyola Professor of Music at College of the Holy Cross (Worcester, Mass.) and a celebrated composer-in-residence with the world-class Chicago Symphony Orchestra. In his exuberant opening remarks, Dr. Golijov said of Mr. Hancock: “If I had to choose one word to define your first lecture last week, that word would be courage. Courage to not take shelter in your stature as a music giant, but to talk to us as a human being communicating with other human beings . . . I was struck by your courage in not shying away from talking about slavery roots nurturing some of America’s greatest music.”

Dr. Golijov then reiterated for the crowd one of the core concepts of the Buddhism Professor Hancock has been practicing for more than 40 years—“turning poison into medicine.” This vital concept, as Mr. Hancock had explained in his initial lecture, entails the transformation of seemingly negative circumstances into vastly beneficial circumstances for all concerned. “You taught us, in such a powerful way,” Dr. Golijov continued, “how there are no wrong chords, only unexpected ones. And how everything becomes part of the music . . . Your ethics, the ethics of jazz are the ethics of life.”

At the top of his lecture, Mr. Hancock announced: “This week, I want to explore the idea of rule breakers . . . the firebrands, rebels, revolutionaries, trailblazers, misfits, pioneers, mavericks, dreamers. Those men and women who, during their lifetime, dare to defy the establishment; question authority and are often ridiculed, vilified, ignored, or sometimes just tossed aside in the process . . . Their ideas were cultivated and advanced by the creative spirit.”

He cited examples from religious history, including Jesus and Moses, as well as the 20th-century founders of the Soka Gakkai (value-creation society), the Buddhist organization to which he belongs.

During World War II, Tsunesuburo Makiguchi was imprisoned in Japan “as a thought criminal. He refused to bend his religious beliefs to an oppressive government and a corrupt religious culture that had given up on matters such as human rights. Josei Toda, his second in command, who was also in prison with him . . . resurrected Soka Gakkai after the war. Because of his work and his mentorship of Daisaku Ikeda . . . today the Soka Gakkai International [promotes] a world religion [of Nichiren Buddhism] practiced in 192 countries with over 12 million members.”

Mr. Makiguchi and Mr. Toda were schoolteachers, and it was Mr. Makiguchi who founded the Soka (value-creation) school system, which, still today, operates under belief that “the focus of education should be the lifelong happiness of the learner—the development of the unique personality of each child with . . . emphasis on the importance of leading socially contributive lives.”

Mr. Hancock spoke about rules from various angles, noting how, whether through their enforcement or the failure thereof, rules have been integral in the evolution of humanity. He emphasized, however, that: “Breaking the rules has to be done with a sense of responsibility. Otherwise chaos ensues. And I think we already have enough chaos in the world today.”

Mr. Hancock spoke about rules from various angles, noting how, whether through their enforcement or the failure thereof, rules have been integral in the evolution of humanity. He emphasized, however, that: “Breaking the rules has to be done with a sense of responsibility. Otherwise chaos ensues. And I think we already have enough chaos in the world today.”

With a nod to the importance and benefit of following certain rules—traffic laws, for instance—he said: “Of great importance, if you break a rule, there are consequences. So it requires ultimate courage to fight for what is ethical.”

Professor Hancock also spoke of how certain rules and laws, because of how entrenched they became in society, even though they were wrong from the outset, are often difficult to change: “From the arrival of the first slaves in the 1500s, it took over 300 years before the 13th Amendment abolished the tragedy and immorality of slavery; our country’s original sin.”

Exhorting the audience to “keep breaking the rules, keep doing the unexpected,” Mr. Hancock also gave his personal definition of a master teacher as one who “has the wisdom to encourage critical thinking and development outside of the anointed rule book.” He spoke of the need for rules “to be flexible to function within the creative aspect of living as a support for change and new development,” emphasizing their capacity to “encourage new possibilities.”

Mr. Hancock acknowledged the collective interest in those who have historically broken or rewritten rules without immediate recognition for their vision: “Einstein, Parks, Newton, Martin King, Socrates, Mandela, Copernicus, Stravinsky, Milk, Presley, Montessori, Robinson, Makiguchi, and the transcendentalists—Emerson and Thoreau—all taught by example, and were ridiculed for their ethics.”

Rounding off a considerable display of cultural references, Professor Hancock quoted the work of renowned science fiction author Robert A. Heinlein, who wrote in his classic, The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress: “I am free, no matter what rules surround me. If I find them tolerable, I tolerate them; if I find them too obnoxious, I break them. I am free because I know that I alone am morally responsible for everything I do.”

Rounding off a considerable display of cultural references, Professor Hancock quoted the work of renowned science fiction author Robert A. Heinlein, who wrote in his classic, The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress: “I am free, no matter what rules surround me. If I find them tolerable, I tolerate them; if I find them too obnoxious, I break them. I am free because I know that I alone am morally responsible for everything I do.”

Future lectures in Herbie Hancock’s “The Ethics of Jazz” series are scheduled to address topics ranging from cultural diplomacy to innovation and technology and to Buddhism and creativity.